Rabindranath Tagore’s Quartet

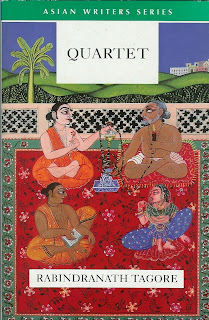

In the introduction to his translation of Rabindranath Tagore’s, Quartet (Chaturanga in the original Bengali), Kaiser Haq states that Quartet “is one of the greatest novellas in world literature.” And Haq, a professor of English at Dhaka University in the Bangladesh and educated at Dhaka and Warwick Universities should know. Haq is considered one of the experts on Tagore, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. The translation was published in 1993 by Heinemann in the UK as part of its Asian Writers Series.

My copy of Quartet has been with me since 1995 by way of Sharmilla Beezmohun, now deputy editor of Wasafiri. It has followed me from Toronto to Tampa and has been on and off my bookshelf. Every time I took down this slim volume (80 pages if you include the translator’s glossary) something always got in the way.

I have written dozens of poems under the influence and even an unpublished novel in which Tagore’s unmatched, Gitanjali is the main character. So it is a puzzle why I had not read this novella before. But yogic realism works in many ways. Returning from Toronto last fall, I fished Quartet off my bookshelf. It has been on my bed-stand until a few weeks ago when I finally completed a first reading. I say a first reading because Quartet is one of those books that deserve a second and a third reading. It is a brilliant book. A first reading is likely to give the impression of a love triangle involving four people.

Yes, I think I got that right; a love triangle involving four people. There is the swami Lilananda and his two male disciples, Sachish and Sribilash, who is the narrator, and the childless, young widow, Damini. Before Sachish and Sribilash became disciples of swami Lilananda, they were disciples of the atheist, Jagmohan—Sachish’s paternal uncle. At the end of the novella, it seems that Sachish is gravitating to a compassionate humanism, a position somewhere between spirituality and atheism.

In the novella, the two young men—graduates in English at the height of British colonial power, and atheists to boot—are trophies for the swami. They live and pray and search for the divine on property owned by Damini’s husband, also a disciple of the swami; he dies and wills the property to the swami with the proviso that his widow is taken care of by the swami.

Damini, the beautiful widow, will not be one of the swami’s disciples. She goes out of her way to provoke the swami. He says time and love will show her the light. And it does like a thunderbolt. Damini means lightening. When the swami and his two prize disciples make plans to go on pilgrimage, Damini shocks them all. She will go, too. It seems that she has finally become a disciple.

The swami and his three disciples set out. One night they camp in a cave. It is pitch black in the cave. In the middle of the night, Sachish wakes to something grasping his ankle. He is scared thinking it is some vile creature and kicks it away. He finds out later that it is Damini. Perhaps, she was also scared in the utter darkness of the cave. Sachish cannot tell Damini he is sorry, or that he finds her attractive. Tagore hints at Sachish’s dilemma. Sribilash, the narrator, however, does not have a problem with spirituality in sensuality, or sensuality in spirituality. His is a different challenge; the object of his longings, Damini, barely notices him, or notices him only when she wants to torment Sachish.

If in the Mahabharata Draupadi had four husbands—the Pandava brothers—with specific visitation nights/days for each, Quartet involves nothing like this. Yet, even in the naming, Tagore seems to be echoing that text. Relations are platonic. But who knows this? Tongues are wagging by the time they return from pilgrimage. The swami remains in Calcutta. The three young people set out. Sachish’s quest is one that goes beyond guru and brilliantly enunciated in the Bhagavad-Gita, the gem within the Mahabharata—“Better is one's own law though imperfectly carried out than the law of another carried out perfectly." History repeats itself; he who forgoes the guru becomes guru, not unlike Gautam Siddartha. To Damini, Sachish now becomes guru. Sribilash follows his friend, or perhaps he follows Damini, who follows his friend, Sachish.

At the beginning of the last of the four sections of the novella, which is titled, “Sribilash” (also the narrator) we learn that Damini is dead. At this point we don’t know that he has married her, or why and how. We get that story now. Perhaps, the essence of this section, and the novella is that Sribilash is not whole without Damini; an affirmation that is at the core of much of Hindu/Indian philosophy. Sribilash married is energized—as is Damini. They are happy. But Damini falls sick. There is no prognosis and no cure. As the doctors prescribe when all medicines fail and as is her desire, they head for a change of air and the ocean. There Damini takes the dust of Sribilash’s feet and before heading for the sea says to him, “My longings are still with me. I go with the prayer that I may find you again in my next life.”

This is the last sentence of this brilliant novella, the most brilliant novella I have read, and a masterpiece. The last words are Damini’s. You could write books on this last utterance. Tagore leaves the reader to interpret, or not interpret.

Readers, depending on philosophies and agendas, will see different things in this novel: a critique of traditions, protests against the treatment of women/widows, untouchablity and caste, hypocrisy… What is undeniable is that this novella is an affirmation of thousands of years of various Indian/Hindu systems and philosophies, some seemingly contradictory, woven in and around a poignant love story—not unlike that globalized Indian tree, the ficus ficus, whose air roots become limbs and trunks and twirl around each other intoxicatingly and in surprising and unsurprising ways. Tagore’s switchbacks in time and sequence and grappling with various strands of India’s complexities within a taut, almost thriller-like, love story bears the imprint of the genius he was.